Backward Course Design: Planning with the End in Mind

NOTE: For more comprehensive information on the topics presented on this page, refer to Modules 3, 4, 5, and 6 in the Principles of Online Course Design Workshop, developed by the St. Kate's Academic Technology team. All instructors are strongly encouraged to enroll in the workshop.

Backward Design Overview

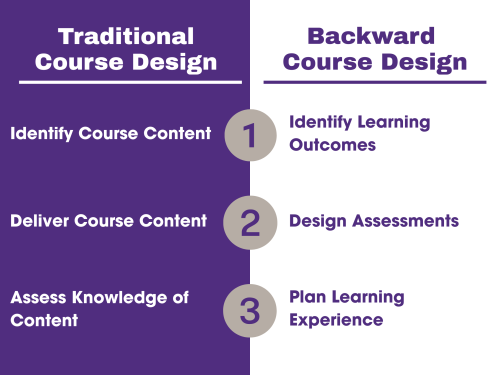

Backward Design is an intentional, student-centered approach to course development that flips the traditional planning process. Instead of starting with content (such as a textbook or list of topics), this method—popularized by Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe in Understanding by Design—begins by identifying the desired learning outcomes.

This framework encourages instructors to focus first on what students should know, understand, and be able to do by the end of the course, aka, the learning outcomes. By beginning with clear learning outcomes, instructors can strategically select assessments and design activities to ensure everything is perfectly aligned—meaning assignments directly measure the intended learning, and course materials directly prepare students for those assignments. This process promotes transparency by making the rationale for all course components clear to students, which research suggests increases engagement and the likelihood that students will achieve the desired outcomes. Ultimately, using backward design leads to a more coherent, effective, and equitable course structure.

The primary benefit of backward design is achieving alignment: ensuring a clear and direct connection between your course learning outcomes, your assessments of student learning, and your instructional activities and content. This alignment increases clarity and transparency for students, which research suggests supports engagement and deeper learning.

Step 1: Write Learning Outcomes

When you create your course student learning outcomes (SLOs), you describe how you want students to change internally as a result of taking your course. Learning outcomes state what students should know or be able to do by the end of a course or curriculum. It is essential to write clear and meaningful learning outcomes so that students understand what they are expected to gain from this course. Meaningful student learning outcomes:

- Are observable and measurable (or otherwise assessable)

- Suit the level and scope of the course

- Take into account the prerequisites

- Align with program learning outcomes/competencies

SLOs are written with active verbs, generally at the critical thinking level (e.g., “understand,” “apply,” “analyze”). Bloom's Revised Taxonomy of action verbs can be used to inform learners about the level of cognitive interaction they are expected to achieve. You can use Bloom's Taxonomy Verb Wheel for ideas about assessment activities that correlate to the action verb. For a more comprehensive list of action verbs (but minus the corresponding assessment activities), see the Revised Bloom's Taxonomy Handout.

ABCD Method of Writing Learning Outcomes

Action verbs aren’t necessarily the only component of a writing objective. You may find it helpful to follow a formula such as the ABCD method when writing SLOs. The ABCD method of writing learning outcomes addresses 4 areas in their construction:

- Audience: Determine who will achieve the outcome.

- Behavior: Use action verbs (Bloom's Taxonomy) to write observable and measurable behavior that shows mastery of the outcome.

- Condition: State the condition under which the behavior will be performed. (optional)

- Degree: If possible, state the criterion for acceptable performance, speed, accuracy, quality, etc. (optional)

Please note that not every learning objective must contain a condition or state a degree.

- LEARNING OUTCOME EXAMPLES

Below are some example objectives which include Audience, Behavior, Condition, Degree

- “Students will be able to apply the standard deviation rule to the special case of distributions having a normal shape.”

- “Given a specific case study, learners will be able to conduct at least 2 needs analysis. “

- “Given a diagram of the eye, students will be able label the 9 extra-ocular muscles and describe at least 2 of their actions.”

- “Students will explain the social justice to ensure that adequate social services are provided to those who need them in three paragraphs.”

Outcomes Versus Expectations

It is essential to recognize the distinction between outcomes and expectations. Expectations refer to what knowledge you expect students to already possess when they enter your class. Outcomes, on the other hand, are the knowledge and/or skills you expect students to learn in the course.

For example, you may expect that students know APA formatting and anticipate that they are applying it in their papers, but your course may not teach it. It’s good practice to minimize how much of a student’s grade is made up of expectations. In other words, you wouldn’t want to have APA formatting count as 20% of a student’s grade on a paper when your course doesn’t teach APA. Also, when incorporating expectations into students’ grades, try to provide resources they can reference, just in case what you are expecting is not something all students have learned before your course. Using our APA example again, if grading on APA, link to the Library’s APA guide in the assignment instructions to provide students with a resource.

Step 2: Develop Assessments

NOTE: The Assessment and Evaluation page of the Faculty Resource Hub provides comprehensive information on assessment methodologies, techniques, and developing assessments in Canvas.

The assessment technique used to evaluate a student's performance may include a paper, project, presentation, test, or discussion board, among others. Generally, assessment techniques are gradable items. There may be multiple ways students demonstrate achievement of a single student learning outcome, or perhaps you will assess students' achievement of one learning outcome through only one assessment technique. It depends on your course design and may be influenced further based on the discipline and your teaching style.

You may also use varied assessment techniques. Which methods are most appropriate for the content in your course and the student skills you need to evaluate?

Pre- and post-testing

Reflection (journals, discussion forum comments)

Demonstrating skills or other observational data (via work submission or video recording; e.g., Physical Therapy students must record transferring a person from a wheelchair to a hospital bed in the lab)

Peer evaluation

Self-evaluation

Authentic assessment (real-world activities), including observational coding

Problem-based and case-study-based action response

Contributions to an e-portfolio (especially useful in areas where evidence of meeting specific standards must be produced)

As you plan the component of course design dedicated to assessment, consider ways to provide additional low-stakes assessment opportunities. For example, consider adding a short quiz that identifies the main points in a reading. For lower-level courses, it is also recommended to break larger assignments into multiple graded segments. For example, a major project in the course requires prior submission of a project plan that includes a description of the components and a timeline for completion, an annotated bibliography of the resources to be used, and a peer review of the draft project prior to final submission.

Regardless of the technique(s), your assessments should attempt to capture the construct(s) you seek to assess. This can actually be a lot harder than it may seem, especially when assessing cognitive skills (as opposed to more easily demonstrable skills, such as an occupational therapy exercise).

While papers might be a favorite method of assessment, it is worth reflecting on whether they are always the best assessment method for you. When papers are used for assessment, consider how not just the topic but the paper style might be used to capture a construct. For example, it might make more sense for a nurse to consult resources to write a treatment plan for a patient with diabetes than to write an APA-formatted research paper about diabetes treatment. Each might have its place, of course—it all depends on the learning outcomes of your course.

Step 3: Develop Course Content & Learning Activities

NOTE: For more comprehensive information on accessibility and Universal Design for Learning (UDL), refer to the Accessibility and UDL page of the Faculty Resource Hub.

Once you have clearly articulated your learning outcomes and decided how you will evaluate students’ progress toward achieving them, the final step is to plan the course content and learning activities.

Course content includes any textbooks, readings, and media you choose for students to engage with, as well as the content you create yourself—for example, your lecture presentations and any overviews, text, and video you develop. An important part of aligning content to your assignments and assessments is limiting or eliminating material that is redundant or unnecessary. In other words, if it does not align with a learning outcome, you probably do not need to include that content.

"Learning activities" refers to the planned exercises that students will do to prepare for the assessment. Learning activities can be done in or outside of the classroom. Outside of the classroom, these activities often include readings or homework, but can also be low-stakes opportunities, such as practice tests or group discussions. Your role is to design learning activities that will lead students to success on the assessment (quiz, paper, project, presentation, etc.), which demonstrates their mastery of the aligned learning outcome.

The most important question at this stage is “How can I create a learning experience for students that encourages them to engage with the content, so that they are truly learning, and not simply passing assessments through rote memorization?” Answering this question involves researching and identifying content that supports students' success on the assessments, as well as determining effective instructional strategies. Of course, you also want content that is timely and relevant, which, depending on your field, may require more frequent updates to the course (e.g., instead of updating readings every three years, they may need to be updated annually).

Engaging students with this content is another matter. Even when content is relevant, this may not be enough to keep students engaged, especially for drier topics or longer materials. Whether you’re teaching face-to-face, hybrid, or online classes, you have many options beyond the traditional lecture approach for presenting course content to help better engage your students.

Step 4: Build the Course

Course alignment is a crucial component of course design, but it is not the only consideration when designing a course in Canvas. Once a course map has been completed during the backward design process, the following steps should be addressed.

Course Design Process Steps

1. Plan the course.

The Course Planning Template may be useful to help you plan your course

Complete a credit audit to prevent overloading the course. You can use this workload time estimator to see how long your planned activities can take

Build a comprehensive syllabus

2. Find and organize course content materials, considering

Copyright permissions

Accessibility. Working with a Librarian to integrate reading lists is a great way to ensure accessibility of course readings

3. Develop and build the course (growing Canvas skills as needed)

Chunk course topics into modules (we recommend weekly modules) with a clear schedule and expectations.

Write content

Create assignments, discussions, and quizzes

Create assessments and rubrics.

Create media elements (e.g., Kaltura lectures)

Ensure all course content is accessible

Build course in Canvas, ensuring to connect content from session to session

Use the Canvas template to make this process easier and to help ensure the course meets essential quality standards

4. The final step is reflection, as course design is an interactive, evolving process, not a static one-time endeavor.

As student demographics evolve, disciplines update and technology use changes, so should your courses. This includes incorporating student feedback and engaging in self-review, peer review, and/or instructional design review. The Quality Standards & Recommended Practices for Online Courses can help with this review.